Tanzimats : Multiculturalism and the Paralysis of Modern Societies

What the Ottoman Empire’s failed reforms reveal about multiculturalism's burden on social cohesion and civilisational agility

Western progressives have been telling us for decades that multiculturalism is ‘our greatest strength’. The Other, with a capital O, is said to bring an alternative vision, an incredible wealth which, through the workings of the Holy Spirit, makes our organisations more creative, our societies more resilient and our economies more dynamic. The contemporary left, and a large part of the soft centre, defend this multiculturalism as a moral and strategic imperative throughout the West, despite its potential side effects. Yet the very modernity they invoke to justify openness actually requires extreme civilisational agility, which multiculturalism prevents: the ability to pivot quickly, to absorb massive disruptions, to maintain a pace of innovation and adaptation that tolerates neither inertia nor excessive fragmentation.

The Ottoman example of the Tanzimat (1839–1876) is a damning historical example: while technical modernity can be imported relatively easily – telegraphs, military schools, railways – social and political modernity, which concerns rights, citizenship, legal equality and centralisation, comes up against a brick wall when a society remains structured into parallel communities that are loyal first and foremost to themselves.

The Ottoman Empire missed out on modernity like few other civilisations have done. Still a giant in the 18th century, by the 19th century it had become a Renaissance empire stuck in the age of the steam engine: lagging far behind in printing, with virtually no endogenous industrialisation, archaic infrastructure, fragmented education and almost no innovation. Nicknamed ‘the sick man of Europe’, it became the ideal prey for the European powers, which carved up its territories, imposed draconian trade conditions and supported internal nationalist movements. Faced with this existential threat, the Ottoman elites launched the Tanzimat: a desperate attempt to catch up with a modernity that they had largely missed. But these reforms were to clash with the ethnic and religious reality of the empire: its lack of a unified national culture and its millet system, which locked them into a rigid mosaic of ethnic and religious identities.

To understand this failure, we must first reiterate that modernity is not simply a catalogue of tools or technological gadgets. It is also, and above all, a truly disruptive cultural and social operating system. Modernity itself is not just a set of techniques and technologies, but also a set of social and societal habits, institutions and beliefs in them. The multiculturalism of the millets, by maintaining parallel community loyalties and freezing identities in legal and social silos, created fatal inertia. As soon as the Tanzimat attempted to move from an empire of differentiated communities to a state of equal citizens, obstacles and sabotage multiplied. While technical reforms went relatively smoothly, social reforms provoked a religious, ethnic and national backlash that accelerated fragmentation rather than resolving it.

This failure serves as a major warning to contemporary Western societies as we prepare to face disruptions of a similar magnitude: widespread artificial intelligence, forced energy transition, and multipolar geopolitical rivalry. This context requires unprecedented civilisational agility. Multiculturalism, elevated to a supreme value in the West, risks becoming the most powerful obstacle to our modernisation, as it once did for the Ottomans.

The Tanzimats show us that we can import railways and telegraphs, but we cannot import national unity, and that the most complicated aspect of modernity to adopt is neither machines nor techniques, but hearts and minds. They also highlight the dangers faced by states that remain on the sidelines of the extreme changes imposed by modernity: decline, humiliation and even extinction.

The “Sick Man of Europe”: An Empire Left Behind by Modernity

In the mid-19th century, the Ottoman Empire was given a nickname that summed up its decline: ‘the sick man of Europe’, an expression popularised by Tsar Nicholas I in 1853. Once a giant dominating three continents, the Sublime Porte had become a colossus with feet of clay, unable to keep up with European industrial modernity.

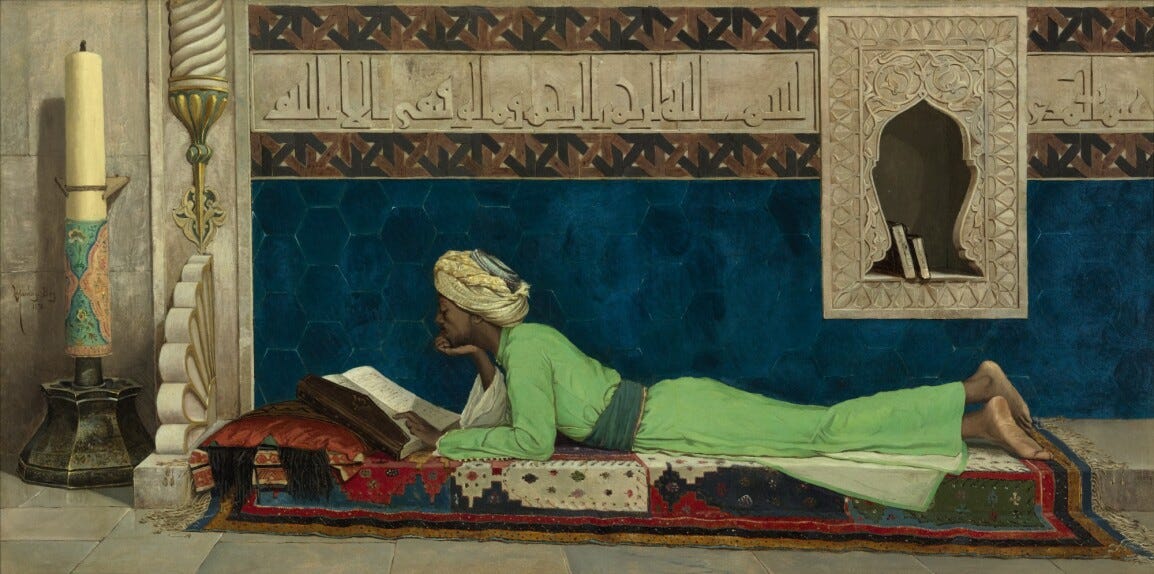

This decline was first evident in territorial losses: Greece’s independence in 1830, Egypt’s de facto autonomy under Mehmet Ali, unrest among Serbs and Bulgarians in the Balkans, and growing demands in the Arab provinces. Each time, the empire lost territory, prestige and tax revenue. Economically, the situation was dire. The empire remained agrarian, dependent on foreign trade dominated by Europeans thanks to capitulations: tax exemptions, consular jurisdiction, derisory tariffs. The Treaty of Balta Liman (1838) opened up the Ottoman market almost entirely to British products, suffocating local artisans. There was no significant industrialisation to speak of: no local steam engines, with the few factories that existed being owned by foreign capital. The empire became an ideal prey for the powers that shared its wealth. The backwardness was also organisational, technical and intellectual. The administration was based on community privileges, not on a rational bureaucracy. Printing in Arabic was only authorised in 1727, under severe restrictions, for fear of damaging the meaning of the Koranic texts. Education, fragmented by religious communities, produced little endogenous innovation: there were few scholars or engineers capable of rivalling Europe.

This weakness can largely be explained by the millet system. Ottoman subjects were organised into autonomous religious communities (Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Jewish, etc.), with their own courts, schools and taxes. This multiculturalism, although pragmatic, ensured peaceful coexistence in exchange for the jizya, a specific tax on non-Muslims that granted them military exemption, while Muslims retained statutory supremacy. Although this brought relative stability to a heterogeneous empire, the profound and structural inequality that this system created among Ottoman subjects prevented the creation of a unified national identity. The millets offered comfortable stability, but at the cost of extreme identity and legal fragmentation. They blocked the emergence of a subject with equal rights and duties. There were therefore no truly Ottoman subjects with a sense of belonging and loyalty to the sovereign and the empire, but only an amalgam of Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish and other communities. How, then, could these minorities recognise themselves as Ottomans and accept the short-term sacrifices required by a major modernisation plan, since they were not Ottomans but members of their minority?

It was against this backdrop of accelerating decline that the Tanzimat reforms were launched. Externally, the powers exploited the ‘Eastern Question’: Russia positioned itself as the protector of Orthodox Christians and Slavic peoples, while France protected Catholics, using the millet system as a lever for interference. Internally, nationalist revolts (Serbs, Greeks, Egyptians, Arabs) and religious tensions were exacerbated. Faced with this double threat, the reformist elites understood that survival required accelerated modernisation.

Technical Success, Social Failure: The Paradox of the Tanzimat Reforms

The Tanzimats (1839-1876) were a brutal attempt to catch up: copying French centralisation and English economic liberalism to save an empire in free fall. It all began with the Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839, which promised security, fair taxation and equality before the law ‘without distinction of religion’. In 1856, the Hatt-ı Hümâyun went further: ending the jizya, giving non-Muslims access to the army and public employment, and establishing mixed courts. In 1876, a constitution was even introduced, establishing a parliamentary monarchy, but it was quickly suspended. The project was clear: to strengthen the central state, partially secularise the law, and integrate minorities into a common civic framework. But it crashed against an unavoidable reality: there was no unified Ottoman nation, but a patchwork of community loyalties jealous of their privileges and identities.

On a technical level, the reforms went rather well. Military and medical schools (1834 and 1838) trained an ‘alafranga’ (French-style) elite whose usefulness was widely recognised. The telegraph was adopted in 1855 and was seen as a tool of central control without any real opposition. Railways were developed, ports were modernised (Smyrna, Beirut, Thessaloniki), arsenals were improved, and a few textile factories were established: all of this took place without too much resistance. Why? Because these changes did not affect the deep-rooted identity hierarchies. Machinery could be imported without challenging the social and identity structures that shaped the Ottoman Empire. These reforms were therefore not a complete failure, at least in technical and technological terms.

But socially and legally, it was a different story. As soon as the statutes, rights and symbols of power that structured Ottoman society were touched upon, the Tanzimat machine ground to a halt. The ulemas, Sunni clerics, denounced a Westernisation that threatened the established order. The secular Penal Code of 1840 was seen as unacceptable: how could a non-Muslim have the same weight as a Muslim in court? How could a Christian in the army command a Muslim believer? The word ‘alafranga’ became an insult used to refer to those who too visibly adopted European manners: ties, hats, table manners, and who by their very nature betrayed their Ottoman identity. Non-Muslim elites were not to be outdone. The Phanariot Greeks, who dominated the Orthodox millet, refused to relinquish their control over the Balkan populations. Promises of equality became a lever for nationalism: Armenians, Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs used them to demand national schools, vernacular-language press and greater autonomy. The promised equality accelerated separatism rather than appeasing it. Tensions exploded: peasant revolts broke out, combining fiscal grievances and community resentment. Mixed courts remained a dead letter, sabotaged by the resistance of traditional judges. Egalitarian conscription, the ultimate symbol of a Christian being able to command a Muslim, was never really implemented. By seeking to centralise power, the Tanzimats weakened the sultan’s authority. They destroyed the old balance of power without succeeding in imposing a new order. The millets retained their de facto judicial autonomy, the provinces resisted reform, and in the end, the central state, which was supposed to be strengthened, saw its power become all the more fragile.

What the failure of the Tanzimats highlights very clearly is that the fundamental difficulty in modernisation, even in the case of ambitious reforms undertaken in good faith, lies not in importing technical and technological modernity, but in adopting social and societal changes in customs and habits. It is fairly easy to import railways and telegraphs. The real problem is social: without national consensus, without a sense of belonging to a community with a shared destiny, it is impossible to gain acceptance for the sacrifices that modernisation requires: higher taxes to finance investment in infrastructure, the army and education, upheavals in hierarchies, and the questioning of community privileges. This is where Ottoman multiculturalism reveals its structural weakness. By maintaining parallel loyalties and sub-national identities, and preventing the emergence of a common Ottoman ‘we’, it undermines the consensus needed to absorb the shocks of transformation. Ultimately, the Tanzimats divided rather than unified, disintegrating the Ottoman Empire rather than enabling it to respond to the challenges of industrial modernity.

The Japanese counter-example from the Meiji era, described in this article is illuminating: a culturally homogeneous society, a strong national narrative centred on the emperor, and a collective will enabled the country to absorb disruptions without internal implosion. The Ottomans, an aggregate of peoples and religions dominated solely by Sunni Turks, were unable to do the same. The lesson is stark: multiculturalism weakens social consensus. It is a major obstacle to the civilisational agility that modernity requires in order to be successfully adopted. The example of Japan shows that national identity and particularities do not necessarily have to be sacrificed on the altar of modernity, but that certain key changes are essential for concrete and successful modernisation, and that these require a strong social consensus. What the failure of the Tanzimats shows is that technology can be imported, but national unity cannot. Without it, modernity cannot take root and remains a superficial technological gadget.

Fragmentation as Inertia: Why Multicultural Societies Struggle to Modernise

The failure of the Tanzimat was not a mere historical accident: it was a final verdict on the real necessary conditions of modernity. You cannot modernise a country simply by importing railways, telegraphs and French legal codes. Nor can you do so by proclaiming equality that exists only on paper. Modernity requires political and civilisational unity that allows for massive and painful sacrifices to be made in the name of a common future. Fiscal sacrifices. The questioning of ancestral privileges. Profound social upheavals. Gigantic investments in education, industry and the army. Acceptance of centralisation that erases local and community particularities. All this can only be achieved if the entire population identifies with the same narrative, the same project, the same ‘we’, the same nation. As soon as the Tanzimat attempted to transform the empire from parallel communities into a modern state made up of equal citizens, the Ottoman population reacted like a grafted organism rejecting a foreign organ. Modernity must not be this rejected graft, but a conscious evolution of the body itself. Instead of unifying and defending the empire, these reforms accelerated the fragmentation of the communities that made it up. They did not modernise the empire; they precipitated its internal implosion.

The West does not need to copy Meiji Japan in order to stay in the race for modernity. But it must remember one simple and harsh truth: multiculturalism, sanctified by the left to the point of becoming untouchable, is not an accelerator of modernity. It is a structural brake on civilisational agility. It disarms the collective ability to make difficult choices. It prevents the formation of the minimal consensus without which no major project can survive the initial turbulence. The Tanzimat still scream this at us through history: we can import technology, infrastructure and laws. But without a strong national identity, without a unifying narrative that prioritises a shared future over community nostalgia, we can never truly bring modernity into our own homes.

We, Westerners of the 21st century, are at a crossroads. General artificial intelligence is arriving at breakneck speed. The forced energy transition will require decades of investment and lifestyle changes. Geopolitical rivalry with powers that are advancing without hesitation (China, India, Russia) leaves us no respite in the pursuit of modernity. All these challenges require the same civilisational agility that the Tanzimat failed to muster: sufficient cohesion to accept immediate costs in the name of future gains, the ability to carry out complex reforms without internal sabotage, and a collective will to project ourselves into a common future. Fast coordination, legitimacy for painful reforms and tolerance for disruption are key if we still want to be key players in modernity, and this is what the fracturation of the national consensus Multiculturalism brings undermines. If we continue to elevate multiculturalism as a supreme value, to celebrate parallel identities as an end in themselves, to reject any demand for assimilation in the name of ‘diversity’, we are setting ourselves up for a Tanzimat 2.0. Technologies will be adopted (they always are). Billions will be invested (the money will be found). But society will be too fractured to accept the sacrifices necessary to become truly modern. Subnational communities will retreat into themselves, local resistance will organise, and national narratives will be diluted by parallel narratives. And we will end up, like the Ottomans, tearing ourselves apart from within while others move forward without us. The multiculturalism dreamed of by the Left is not our greatest strength but a divisive factor that prevents us from devoting ourselves to the pursuit of progress and prosperity. And, having failed to promote a national unity of destiny allowing us to be modern, we risk suffering the same fate as the Ottomans: first decline, then humiliation and at last, dissolution.

One of the most striking aspects is how reforms often fail not because societies resist change, but because intermediary elites have little incentive to support reforms that would dissolve their privileged position.

Modernization can threaten elites long before it empowers majorities.

Thank you for the article, it draws some interesting points as do many of the comments. I see Europe's problems as having multiple dimensions, with only partial parallels to the case of the Ottomans: composition, political authority, established interests, sun-"national" administration, global context. In then Ottoman Empire the Sunni Turks were a pluraity minority, and unlike the Hapsburg Austrians they weren't indigenous to the space they came to dominate. To the established population's if the Balkans and Anatolia they were seen as illegitimate: Muslim invaders that had to be evicted like with Iberia (and rebellions were a constant feature throughout Ottoman history). Even amongst the Muslim Arabs the Turks were viewed as exogenous: barbaric nomads, uncultured and not real Muslims. During the Tanzimat reforms slavery was still ongoing for non-Muslims. The history and composition of the empire didn't favour secular republicanism, and the Turks lacked the authority to implement it: political, historical and technical/administrative- they were viewed as incompetent and were already in the 2nd century of constant defeats by neighbours. This was made worse by the banning of the printing presses in prior centuries for Muslims who thus faced mass illiteracy, while Christians and Jews were pulling ahead in the 19th century due to literacy and multilingualism. This was deeply resented by Muslims, who viewed themselves superior and led to deadly pogroms and riots: the Muslim was superior, the infidel was vile and had to pay hommage and Jizya (in his ancestral lands!). For nationalist reasons the local administration was anti-national, no regional authorities with compétences other than exploitative tax-farming, who were seen more as sellouts and collaborators to the oppresers. Contrast this with the Hapsburgs, who had administrative authority, shared religion, greater meritocracy and competent regional elites. The situation in the "multicultural" EU is quite different: nation states are legitimate, but the elites are losing legitimacy due to swlf-serving politics that fail and so they retreat to Brussels to add a super-national layer of defense from public cries for changes. There is a well educated population that has a huge intergenerational transition to make (less pension spending, more investment, break up rent-seeking cartels, streamline administrative state). Too many comfort zones have to be popped, but hard budget constraints will pop them anyway and the choice will be true reform or return to feudalism (as happened here in Greece after 2010).